AI and Human Judgment

Judgment and algorithmic decision-making are complements, not substitutes.

I attended last weekend’s Troesh Entrepreneurship Research Conference which featured a number of outstanding papers on AI and entrepreneurship. (Catching The Eagles at the Las Vegas Sphere wasn’t bad either.) Many of these papers will appear in a forthcoming Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal special collection on this topic. Indeed, the last couple of years have seen an explosion of interest among researchers in how AI affects, and is affected by, entrepreneurship. This includes broad, conceptual, overview papers, reflections on specific issues such as Knightian uncertainty, and empirical studies on how intelligent agents perform in proposing and evaluating projects, how AI exposure affects the cost of entrepreneurial entry, and more.

A more fundamental issue is whether generative AI can “do” entrepreneurship (or strategy or other senior management functions). My own view, rooted in the judgment-based approach, is that intelligent agents can exercise what Nicolai and I call “derived judgment”—performing tasks, even complex and creative ones, under the supervision of a higher-level authority—but not “original judgment,” the residual authority that comes with ownership and ultimate responsibility. As Ludwig Lachmann (1956) put it, in the context of owners and hired managers, even those with substantial day-to-day decision rights: “We might . . . distinguish between the [owner] and the [manager]. The only significant difference between the two lies in that the specifying and modifying decisions of the manager presuppose and are consequent upon the decisions of the [owner]. If we like, we may say that the latter’s decisions are of a ‘higher order.’”

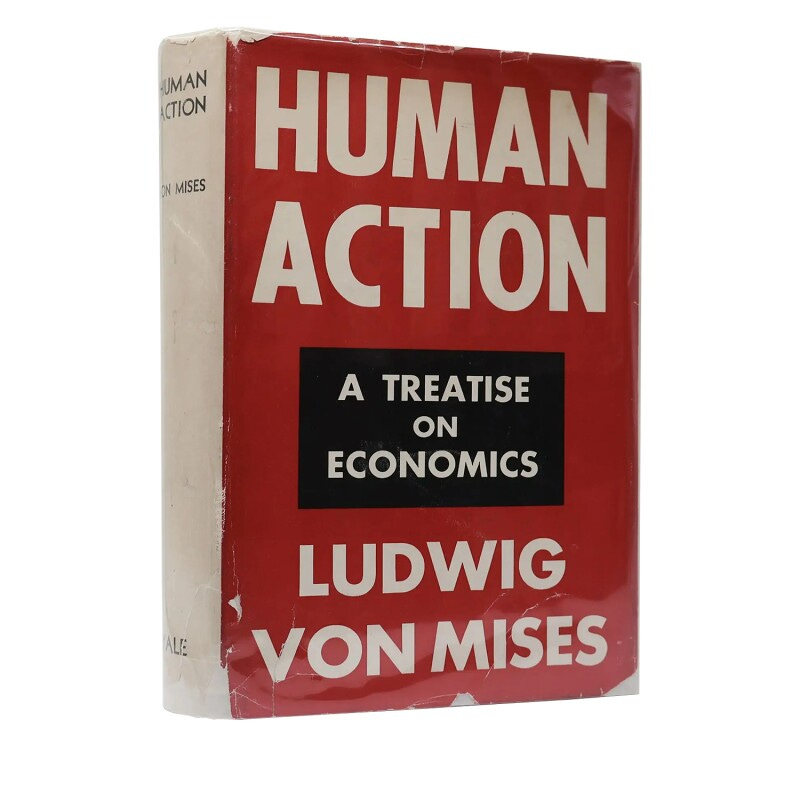

In the present context, this means that an LLM (for example) can perform a variety of functions that look like entrepreneurship, but only because a human entrepreneur has empowered the agent. Someone has to choose which model to use, what prompts to provide, and whether to act on the results. (As we’ve learned, when agents try to generate their own prompts, the results quickly degenerate into gibberish.) An AI agent cannot hold residual rights of control, in the language of property rights economics. Machines can carry out tasks delegated to them but cannot decide what tasks to delegate, to whom they should be delegated, whether the task is worth performing, how to adapt these arrangements in the face of unforeseen contingencies, etc. More generally, algorithms cannot—at least today, maybe not ever—engage in what Mises calls human action: deliberate, purposeful, goal-oriented, volitional behavior, including intuition, judgment, initiative, and responsibility.

David Duncan, writing this week in Harvard Business Review, agrees. He argues that AI and human judgment are complements, not substitutes.

This makes sense when you look more closely at how people actually get good results when working with AI tools, which requires constant evaluation of what it’s giving you and thoughtful iteration. You prompt AI, get a result, assess, then re-prompt it, making small course corrections as you go.

Historically, that kind of judgment does not come from using AI. It comes from having done work similar to what you’re now using AI for and learning from the sometimes poor, slow, imperfect experience of repetition, with real responsibility for the outcomes sharpening your focus.

This leads to a paradox organizations are now confronting, whether they realize it or not: AI simultaneously increases the need for judgment and erodes the experiences that produce it.

His definition of judgment echoes that of Knight, Mises, and other contributors to the judgment-based approach (JBA): “Judgment can be defined as the capacity to act wisely in situations where rules by themselves are insufficient—by recognizing what matters most in a situation, weighing competing priorities and tradeoffs, anticipating consequences, and deciding when to personally own a choice under uncertainty.”

There is a difference, though. The JBA defines judgment as the act of judging, i.e., making decisions under conditions of Knightian uncertainty. (The latter can be operationalized as an open set of potential outcomes, an unknown state space, sheer ignorance, and the like.) Duncan is talking about good judgment, i.e., wisdom, prudence, discretion, etc. Judgment per se can be good or bad, though there are reasons to believe that market competition selects for good judgment such that those with superior judgment will tend to survive and thrive, while those making worse judgments will tend to be selected out.

Duncan points out a paradox: “To use AI effectively, people need judgment about the task at hand, but as AI takes over more of the work, the very experiences that once produced judgment start to disappear.” Moreover, “[o]rganizations depend on a steady replenishment of people who can make sound decisions under uncertainty. Historically, that replenishment happened as people moved through roles and accumulated experience with increasingly consequential choices. . . . As AI automates formative work, fewer people will encounter the situations that once served as training grounds for judgment, with the result that it becomes concentrated in a smaller group of senior leaders whose experience predates widespread automation.” Without providing a solution, he asks some provocative questions organizations can ask about how their practices and procedures select for, or impede, the development of good judgment among managers and employees.

His conclusion: “The defining challenge of the AI era is how to continue to produce people capable of exercising judgment.” I could not agree more!

Couldn't agree more with your points. Another piece to this is that yes generative AI can generate a ton of output (so it's highly efficient), but that doesn't mean that any of it is actually valuable (so it's ineffective).

I've been working on an applied project synthesizing the ideas of the Judgment Based Approach specifically for busy executives. I've combined it with my retrospective experience working "in the trenches" at Uber and Lyft where I often found myself to be "the one economist in rooms filled with data scientists." Here's an article from that series that overlaps very well with yours here. https://www.economicsfor.com/p/entrepreneurial-judgment-and-ai-precision

(P.S. You may remember me from Mises U and AERC years ago. Last we saw each other was in Reno at the Hayek Group talk you gave hosted by Mark Pingle where Mark Packard also attended. My younger brother Steven Spurlock was a student at this year's Mises U too).

Peter, may I take you on a slight tangent? C. S. Peirce defined three types of reasoning: deductive, inductive, and abductive. Deductive reasoning is the essence of LLM operation over massive stored data. Both inductive and abductive are ampliative reasoning, when the boundaries of the prior data are breached. I wonder if AI can eventually (soon?) do inductive reasoning. I believe that the initial conjectures, hypotheses, or hunches that populate abductive reasoning must remain vested in human agents, like entrepreneurs.